‘It’s the freakiest show’: David Bowie’s Artistic Legacy

Megan Ballantyne considers David Bowie’s artistic and cultural legacy, from the 1970s up to present day.

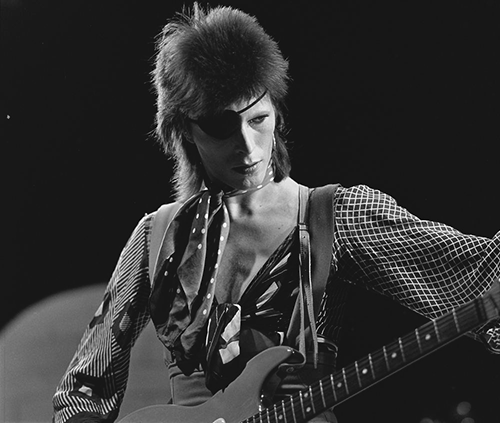

To many people, Bowie was the 1970s. While the decade officially began at the start of 1970 like any other, the aesthetics and sound of the era, the alternative voice of mainstream society, was truly found in the 24-year-old David Bowie, when he debuted his most popular character, Ziggy Stardust, in 1972. In David Bowie’s succession of psychedelic characters, he created a cultural movement through his modern, often space-themed aesthetics, which allowed him to both exist within and critique mainstream media and society.

David Bowie used his performances to challenge the visual and aesthetic conventions of the 60s, which centred around the idea that ‘authenticity’ was desirable from media. In the music industry, this created music made from ‘real instruments’ and performers who were focused primarily on creating meaningful music rather than on their visual aesthetic. Bowie, however, challenged this idea that good music required limited production through his performative ‘characters’ who were visually arresting and sung songs filled with synthetic background noises. These larger than life figures were instead designed to represent excess and modernity.

While Bowie’s first character, ‘Major Tom,’ used sartorial items such as a spacesuit and spacegear to reflect his character’s profession as an astronaut, it was with Ziggy Stardust that fashion really took centre stage. Here, fashion became an expression of the complex character of Ziggy himself, a symbol of the ‘superhuman’. Ziggy Stardust was an alien sent to earth, and Bowie communicated his other-worldliness through making him visually ‘strange,’ dressing himself in colourful jumpsuits and wearing bold, glittery makeup on skin painted sheet white. The androgyny and ‘outrageousness’ of these sartorial choices shows that Bowie crafted his image in opposition to cultural norms of the 1970s, when most people had relatively binary conceptions of gender. When Bowie’s enormous popularity meant that he entered the mainstream, these controversial fashion choices and their inherent criticism of gender norms in western culture encouraged the widening of cultural discourse around gender identity and expression.

In David Bowie’s succession of psychedelic characters, he created a cultural movement through his modern, often space-themed aesthetics, which allowed him to both exist within and critique mainstream media and society.

A key symbol of Bowie’s androgyny was his bright red mullet, a hairstyle which he was one of the earliest adopters of. It had both the length of a typical ‘woman’s’ haircut at the back but was also a short ‘masculine’ cut at the front. This meant that it was worn by men and women alike, and has filtered down through the years to also become an integral part of the Exeter University experience in 2021.

Bowie took much inspiration from visual artists in his approach to society and societal criticism, including Andy Warhol. Warhol was a contemporary artist, who created series of images of mass-produced items as a comment on the commericialisation of society. Through his lyrics, Bowie likewise criticised the commercial spectacle of the modern entertainment industry; media in Life on Mars is depicted as a technique to distract people from their everyday tragedies by making spectacles of fictional lives. Bowie, like Warhol became a part of mainstream culture and a critic of it, and this contradiction can be observed once more in his approach to fashion. His clothes were often made from synthetic fabrics and ‘mass-produced’, but they were also incredibly unique, even asymmetrical. Bowie’s style was, therefore, a symbol of hypermodernity much more so than of commercial mass production, just as Bowie himself was an individual artist first, a popular megastar second.

In comparison with the visuals of his performances and characters, David Bowie’s personal ventures into physical art such as paintings made an extremely limited cultural splash, but it did reflect the man’s own approach to art as a dynamic, evolving form. Nonetheless, if Bowie’s visual art and fashion had existed in a vacuum, it could not have created the same cultural fascination. It was Bowie’s synthesis of his artistic visuals with otherworldly lyricism and music production which produced the cultural era which was David Bowie, which successfully walked the line between man and character, art and existence, authenticity and popularity.