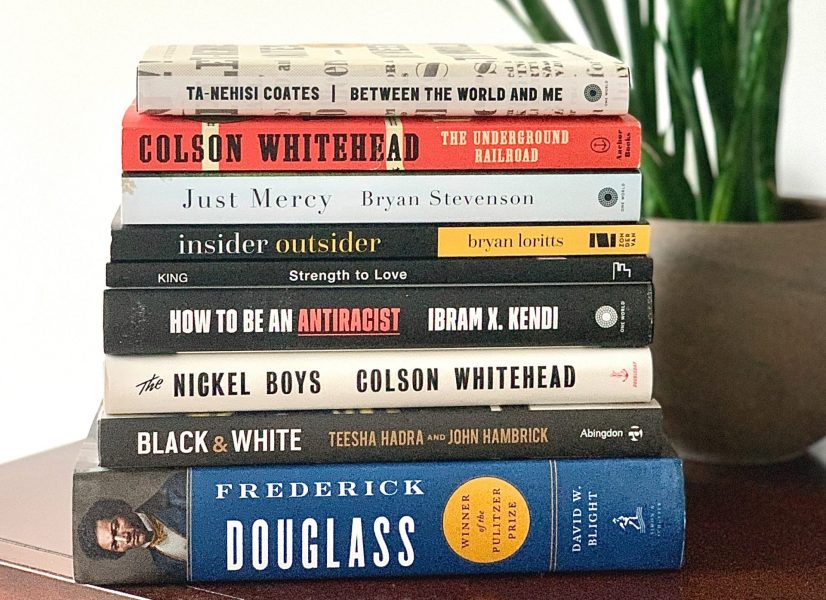

Black History Month mini book reviews

In celebration of Black History Month, two Exeposé contributors share their book recommendations. Catherine Stone discusses Noughts & Crosses by Malorie Blackman and Clémence Smith reviews The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead. Beware: spoilers ahead!

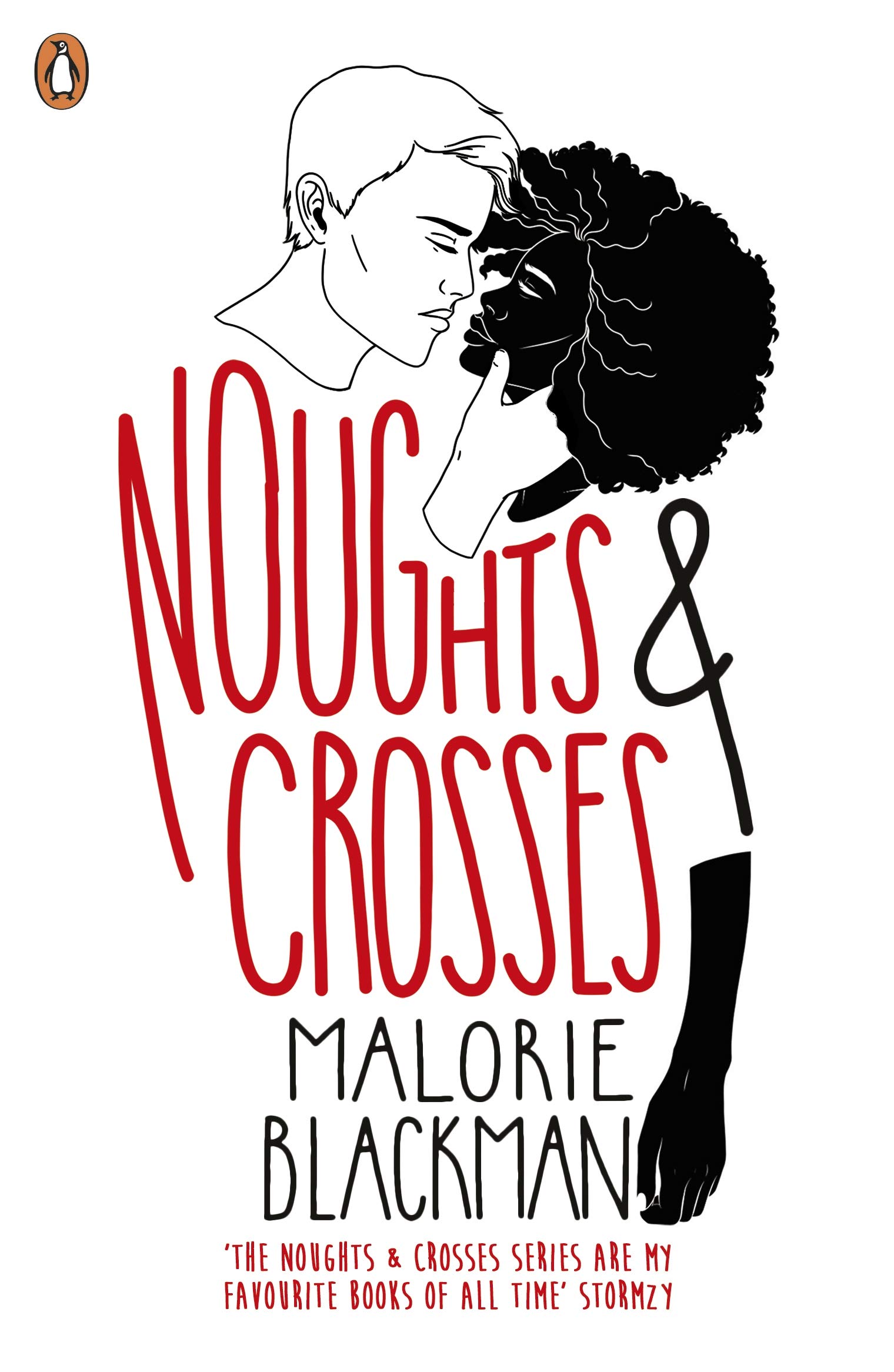

Noughts & Crosses by Malorie Blackman

Published 20 years ago, Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman remains a landmark text in the development of both teen literature and fiction that confronts racism and oppressive class systems. It stands as a groundbreaking modern classic that has had a strong impact on British consciousness. It was named one of the BBC’s 100 Novels that Shaped Our World and is commonly found on school reading lists.

In this alternate reality novel, Blackman imagines a world in which Aprica (Africa) colonises Albion (Britain) and establishes a hierarchical system in which the black Crosses retain an elevated status above the oppressed white Noughts. By subverting expectations, Blackman makes full use of the power of fiction to explore prejudices and examine human nature from an interesting and engaging point of view. She charts the sweeping love story of protagonists Sephy, a rich Cross whose father is deputy Prime Minister, and Callum, an ambitious but poor Nought, and their fight against the draconian laws of their world.

Noughts and Crosses boldly tackles themes such as terrorism and extreme racism, making it an important book for teens as it generates discussion around things they may not have analysed before. Blackman draws on current events and her own experiences to create a realistic picture of this world. Her initial motivation for writing the book came from the unjust investigation of Stephen Lawrence’s murder. The book’s ending, in which Callum is hanged, highlights society’s inability to change.

The subsequent books in the series express the continuing hope for a just society in the characters Callie Rose (Sephy and Callum’s daughter) and Tobey, her Nought friend. Their eventual triumph over obstacles and pain to happiness and success in law and politics respectively ends the series with a positive view of the future.

I would also highly recommend the recent BBC adaption as a powerful expression of the book’s key ideas; the visual medium allows for complete immersion in the world. The excellent writing and older characters make it a great watch for young adults.

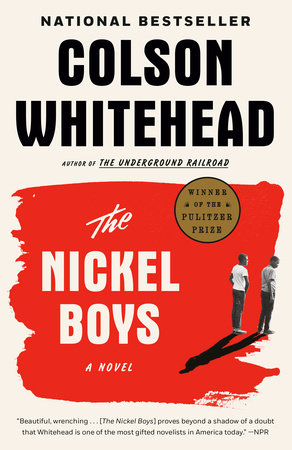

The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys is by no stretch of the imagination a pleasant or light-hearted read – one could argue, however, that this is what makes it so brilliant. The plot follows Elwood Curtis as he is framed for travelling in a stolen vehicle and sent to a juvenile reform centre called the Nickel Academy. Published in 2019, the book has won a plethora of awards, not least of which being the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Whitehead is one of only four authors to have won the Pulitzer Prize twice: The Underground Railroad, published in 2016, was awarded the prize in 2017.

Whitehead masterfully juxtaposes past and present, highlighting the long-lasting consequences of the abuse Elwood endures. The corruption present within Jim Crow America sends ripples through history that are still prevalent today. The reader has to confront past events that have too often been swept under the rug, making the book as eye-opening as it is horrifying.

Interestingly, the system reveals its hypocrisy by calling the boys “students”. Although this name implies self-agency, the boys in the academy are brought there by force and can only leave when the adhere to societal norms. The hegemony establishes a false sense of homogeneity among its victims; the reality is, however, that their experiences differ greatly depending on the colour of their skin. Their bodies become imprints of violence as the boys’ scars mark the consequences of the injustice they endure.

As Elwood remarks: “you could walk around and get used to seeing only a fraction of the world. Not knowing you only saw a sliver of the real thing”. Although the contents of this book are shocking, the discomfort one feels is an unavoidable part of seeing “the real thing”, the world in its entirety. By unearthing and listening to marginalised voices, we become better equipped to tackle the problems our society faces.