2021 Nobel Prize in literature

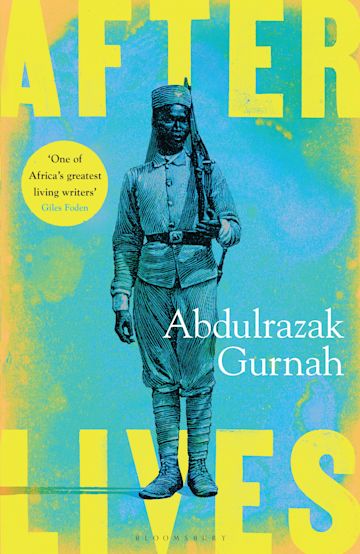

Abdulrazak Gurnah, winner of the 2021 Nobel Prize in literature, has surged to the top of bestseller lists. Catherine Nock reviews his latest novel, Afterlives, and discusses the impact of receiving such high critical acclaim.

If there’s one writer who will be experiencing a significant spike in Google searches and book sales, it is Abdulrazark Gurnah – academic, novelist, and recipient of this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature. By the afternoon of the announcement, I had triumphantly managed to track down a copy of Gurnah’s Afterlives. The postcolonial novel was published last year and, like Gurnah’s other works such as Paradise (1994) and By the Sea (2001), deals with the stark, bloody consequences of colonial rule and dislocation, exploring how outside forces shape inner lives.

From the outset of Afterlives, Gurnah foregrounds the tensions in a politically fraught German East Africa (now Tanzania), heavy with the marches of the Schutztruppe as they reinforce colonial rule. Occupation, trade embargoes, and violence that leave the land ‘soaked in blood’ form the context of his young protagonists’ lives, who are forced to grow up in an ever-changing world. Some characters, like the charismatic Ilyas, initially seem to fall on the ‘right side’ of history – favoured by the Germans and gifted with both literacy and a job thanks to precarious, stumbling sequences of goodwill and luck.

Gurnah chooses to focalise the narrative through the eyes of several characters; as the novel continues, we see how the characters’ lives intertwine, like tracing back the strands of a frayed piece of string. In a moment of dramatic irony, volunteer recruit Hamza hears the news of a war being passed around the camp in whispers, signalling the start of World War One: tragically, he has no idea of the scale of the impending conflict.

As the novel continues, we see how the characters’ lives intertwine, like tracing back the strands of a frayed piece of string

Gurnah’s work has received the Nobel Prize for ‘his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents’. The idea of a ‘compassionate’ examination is interesting: Gurnah has said that he grew up with these stories and that his primary interest was not to write about ‘the ugliness of colonialism’, but rather to explore how people cope with the context of war. His characters carry much of this weight: they are convincing and honest.

What does the award mean for its winners? We can see it happening right now: a great surge of interviews, tweets, and agents’ calls as Gurnah’s work is brought to a readership that is rapidly expanding, global, and buzzing with high expectations. However, there is potential for such an achievement to burden the creative method and taint the motivation behind writing. When interviewed in 2020 about his hopes for Afterlives‘ impact, Gurnah somewhat avoids the question, and instead replies: ‘I write about these things because this is what engages me, this is what I care about.’ The response shows an admirable distance from worrying about what the readership will think – however, it may be difficult to maintain in this new climate of interest. It’s the Nobel Prize, after all, and it inevitably captures public interest; it’s not every day that art becomes breaking news.

What’s more, in the vibrant internet ecosystem of retweets, click-me headlines, and book-vlogs, the anticipation for the next novel is likely going to rise. However, if there are any books that need to be brought to light, it is books like these – works that deal with parts of history often glossed over by the curriculum.

The Nobel Prize in Literature offers a unique platform for authors’ ideas to be discovered by an international community of readers, and to spark new conversations. Written in a refreshingly clean and direct style, Gurnah’s works quietly ask us, while we read, to rethink our understanding of history: both of who writes it, and how we read it.