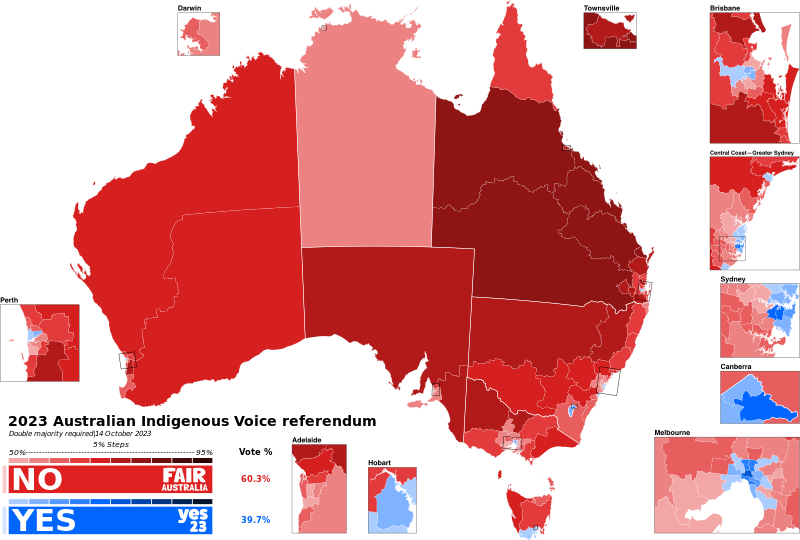

A recent Australian referendum, which proposed the official constitutional recognition and increased democratic representation of Australia’s First Nation peoples, has resulted in an overwhelming ‘no’.

The proposal was rejected in all six Australian states – with the least support coming from Queensland – where only 31% voted ‘Yes’.

For centuries, Australia’s indigenous peoples have suffered shorter life expectancy, lower quality education and worse healthcare outcomes than the non-indigenous population. The ‘Yes’ campaign hoped success in the referendum would help ‘close the gap’.

For centuries, Australia’s indigenous peoples have suffered shorter life expectancy, lower quality education and worse healthcare outcomes than the non-indigenous population.

The defeat was met by a week-long ‘vow of silence’ by the indigenous people to process the devastating results.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said that he must respect “the democratic process” despite his personal disappointment with the outcome.

The need for the Aboriginal people to become fully integrated into Australian society has always been a major issue for them, especially since the ‘2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart’. The Statement was an invitation to non-indigenous people to help in the reform of their rights and to establish an Indigenous voice within Parliament. After six years of pushing, the ‘Yes’ campaign finally achieved a referendum, only to be met with this disappointing result.

The First Nation people have lived in Australia for over 60 000 years but are not included in the country’s constitution – their wish is to no longer be a forgotten population due to past colonisation. This referendum is the 45th attempt to change Australia’s Constitution, (not all been indigenous-related) but only 8 have been accepted and put forward.

This campaign has been defaced with racist remarks and the belittling of the requirement for First Nation representation in government. A key victim of online hate was prominent ‘Yes’ campaigner ‘Thomas Mayo’ – who was featured in a racist cartoon from Fair Australia – the leading group in the ‘No’ camp.

Fair Australia, amongst other organisations, is against representation of First Nations people because they believe that it would divide Australians by race, rather than accept all of its citizens as equal.

“Australia has overwhelmingly voted for a nation that is one together, not two divided” said Advance Australia, a conservative political lobbying group. As well as fear of division amongst its peoples, ‘no’ campaigners and voters believe that it will not solve the issues that indigenous communities face, and that a form of ‘treaty’ would be better to define the relationship between The First Nation communities and its countries’ government. This idea comes from Aboriginal Senator Lidia Thorpe and the Blak Sovereign movement who would prefer not to be mentioned in such an ancient constitution, but instead find other, legally binding ways to find equality for the First Nation and Torre Strait Islander people.

The international reaction has largely been one of shock, with many expressing sympathy for the indigenous peoples and some describing the decision as having racist undertones.

A group called Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (Antar) has reeled from these disappointing results but said that they would not give up the fight for the key aims of the Uluru statement to be put into practice (voice, treaty, and truth.) The Guardian took a quote from Antar which states that they “don’t accept that this is the end of the movement for change. The voice was only one mechanism for progressing First Nations rights and justice.”

“[We] don’t accept that this is the end of the movement for change. The voice was only one mechanism for progressing First Nations rights and justice.”

Antar

This was the second attempt for Aboriginal recognition in the Constitution after a failed attempt in 1999, and this further defeat has created a sad atmosphere for many in Australia at the moment.

This referendum was not about race, there was little risk of division in the country had the ‘Yes’ campaign succeeded – it simply would have meant indigenous voices would finally be heard and taken seriously at an institutional level. Antar and other indigenous leaders took a risk when advocating for such a change in government, and were met with not only defeat, but shameful racism and discrimination as well.