Last week I had the pleasure of interviewing Katie Partridge, who completed her PhD at Exeter studying diabetes and is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Exeter. In our discussion, Katie highlights the skills needed to complete a PhD, and how scientific research is a global, not individual, pursuit.

O: What was the focus of your PhD?

K: My PhD was focused on AMPK activators, so on an energy-sensing protein within alpha cells in the pancreas. They secrete glucagon and my supervisor and I focused on whether we can pharmacologically target the alpha cell to boost glucagon secretion and restore glucose levels in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. My research has been focused on diabetes for 5 years, since my third year of undergrad.

The work I’m doing now is slightly different from my PhD, I’m working with two PIs. Both areas of work are focused on developing new technology for the treatment of type 1 diabetes.

O: Was there a specific reason for choosing diabetes research? Did it start as a random project allocation or is there a backstory?

K: It was a bit of a random coincidence, actually. During my second year, I was uncertain about what to do for my placement. A lecturer helped me navigate my options. I knew I was interested in hormones, so I explored various pathogenic contexts, like diseases with associated charities and funding for research projects. Diabetes research caught my attention, I didn’t know much about it. Interestingly, several of my family members have experienced diabetes, so there was a familial connection.

I went to Diabetes UK’s website, which is the UK charity for diabetes, and checked the list of projects they were funding at the time. The first one that caught my eye was Professor Noel Morgan’s project. I sent him an email, came here for a year, and fell in love with studying islets of Langerhans, understanding how it functions, and figuring out how we can best research and target it to potentially cure diabetes.

O: What are your hopes for your diabetes research, from your placement year to your PhD and your current work? How do you hope this will impact people with diabetes?

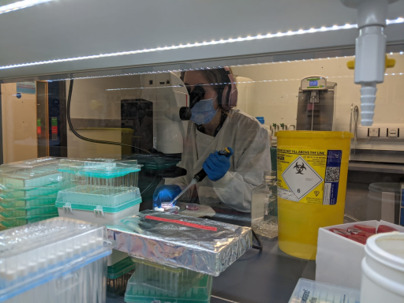

K: In terms of wet lab research I’ve done, I’ve focused on characterising the response of several pharmacological drugs that are in testing, so not clinically available yet, in alpha cells. These drugs have therapeutic efficacy, so they have very similar mechanisms of action to some compounds that are already on the market to treat diabetes. Learning about these drugs and how they work in different tissue types can paint a better picture of who these drugs would work for, and what stage of diabetes they would best treat. That’s why the work has a lot of promise because it aids the rest of the field in understanding diabetes from a whole-body perspective rather than just a tissue perspective.

‘It’s a collective team effort across the world’

Research is peer-reviewed and should be replicable. Science, therefore, should be a collective and collaborative, team effort in order to pave a breakthrough. It’s a collective team effort across the world. It’s a bit like stacking plates, you can put lots of information together and learn a lot from it.

O: How did you get into academic research? Was it always the plan?

K: I got into research, as I mentioned before, through my placement. I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to do, which I think lots of people experience. There are so many options waiting for you at the end of your degree, and it can be hard to tell which is the right path.

I came to Exeter for my placement year and enjoyed the research. I liked being busy and designing and doing the experiments, I found that invigorating. I also found that I really enjoyed working with beta cells, and later on, other pancreatic endocrine cells, and so then I knew that I wanted to do a PhD because I wanted to research further. I hope to continue with my research because I think it’s amazing to be able to learn about all these different projects and be at one of the centres for diabetes research.

O: Would you say that Exeter is one of the centres of diabetes research?

K: I think it’s one of the leading research centres for diabetes in the UK, especially for the likes of monogenic diabetes and genetic research. But that’s not to take away from the wet lab work, which is well known because I think we’ve got one of the largest banks of fixed human pancreatic tissue. We have a good depository of tissue to work with and investigate type 1 diabetes with.

O: Is there anything you’d known about your own research before you began?

K: I was a bit naïve to think that all experiments would be successful, that it’ll be A to B and you’ll get data. That does happen often, but there are a lot of steps and a lot of planning to get from A to B before you’ve actually done the experiment itself. It would have been beneficial to know that a lot of experiments don’t work the way you want them to.

That being said, there’s always a take-home message from negative results. Even when people say that their experiments have failed, there’s usually something you can take from it. For example, if a piece of equipment malfunctions, and if you can figure out why that has happened, you can go back and fix it. There’s always something to learn from and always something positive to move forward with. That was a big learning curve I had and maybe something I should have understood from the beginning because it can be quite a negative experience when experiments go wrong. It’s annoying, but you’ve got to move forward.

O: You’ve got to persevere.

K: Oh yeah, definitely. Perseverance is a huge quality you need going into research, especially because you’re spending the whole 3-4 years of a PhD on the same project. You’ve got to investigate one thing for a very long time and so if your experiments at the beginning don’t work as well as you want them to, you need to have perseverance and problem-solving to be able to figure out what’s going on. But the biggest personal changes and learning experiences you get are from when things go wrong, it builds your character as well.

O: As a final question, what advice would you give to someone entering research?

K: You want to make sure that you’re in a good, supportive environment. It’s worth reaching out to the team beforehand and seeing if they run any socials or anything to make a more cohesive environment. Look beyond the PhD and at the area you’ll be going to. It’s beneficial to go to a city with a good work-life balance in case the project doesn’t go well.

Make sure you’re interested and invested in your PhD, and it’s not just something you’ll be interested in for a little while. You want to make sure you’ve got a deep-rooted interest in it. Research the experimental techniques you’ll be using and decide whether that will be of interest to you. Don’t do a PhD because it feels like the next step. A PhD is a marathon and not a sprint, whereas undergrad can feel like a sprint and not a marathon. It’s about taking your time and making sure it’s right for you.

For questions relating to next steps into academic research, Katie can be contacted on, k.partridge2@exeter.ac.uk