Scientists have found that Zosurabalpin defeated strains of Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (Crab) in mouse models of pneumonia and sepsis. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Crab is classified as a priority 1 critical pathogen that, while not aggressive, is resistant to numerous different antibiotics. It is very difficult for new treatments to be developed against Crab because of the bacterium cells’ efficacy in preventing antibiotics from getting past its outer layer.

Antibiotic-resistant infections pose an urgent threat to human health; WHO corroborates this, describing that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens “to send modern medicine back decades to the pre-antibiotic era, when even routine surgeries were hazardous”. AMR increases the risk of bacterial infection spread – particularly those caused by a large group of bacteria known as Gram-negative bacteria, which are protected by an outer shell containing lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

“LPS allows bacteria to live in harsh environments, and it also allows them to evade attack by our immune system,” said Dr Michael Lobritz, the global head of infectious diseases at Roche Pharma Research and Early Development in Basel, Switzerland, which developed the new drug. Through myriad experiments published in Nature, Professor Daniel Kahne and his colleagues at Harvard University have concluded that Zosurabalpin is the first antibiotic to prohibit the movement of LPS from the inside of a bacterium to its outer membrane, killing it. The antibiotic was also found to reduce the number of bacteria in mice with crab-related pneumonia and reduced the death rate of mice with crab-induced sepsis. This is promising for the prospect of human trials.

This discovery could pave the way for the use of this mechanism of action against the same LPS transport system in other bacteria

Dr Lobritz, however, emphasised the limits to this drug; Zosurabalpin alone cannot eradicate the globally significant health threat that is antibiotic resistance. Nevertheless, this discovery could pave the way for the use of this mechanism of action against the same LPS transport system in other bacteria.

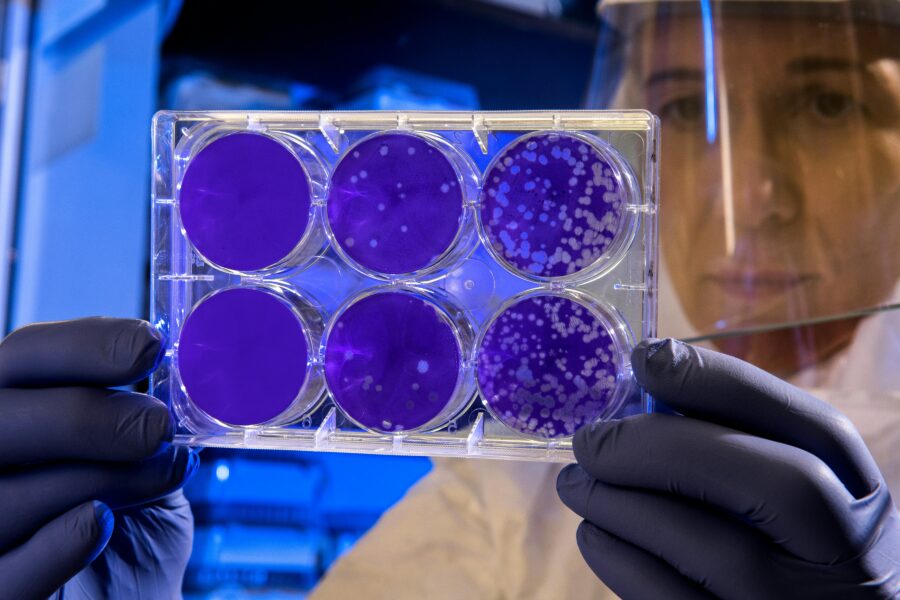

In the meantime, another approach has emerged to tackle AMR. The UK’s science, innovation and technology committee has called for steps to develop the potential of bacteria-killing viruses – called bacteriophages – that could provide an alternative to antibiotics for resistant infections. Phages are viruses that can target individual bacteria. They replicate and infect the bacteria inside and cause bacteria cell lyses (in other words, their cell membranes burst). This removes bacterial defences reducing their effectiveness to ultimately minimise the bacteria’s resistance to antibiotics. Phages’ clinical use is currently restricted by UK regulations: in a report published on 3rd January, the committee said development of phage therapies had hit an “impasse” because investment in manufacturing phages hinged on successful clinical trials.

For this revival of phages as an antimicrobial, the government must approve the deployment of phages in clinical trials, manufactured to the Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) standard. The committee is asking the government to consider Rosalind Franklin laboratory in the West Midlands, which was originally set up to process Covid tests, as a suitable facility for phage manufacture. This would be a positive step towards the role of phages in the national approach to antibiotic resistance.