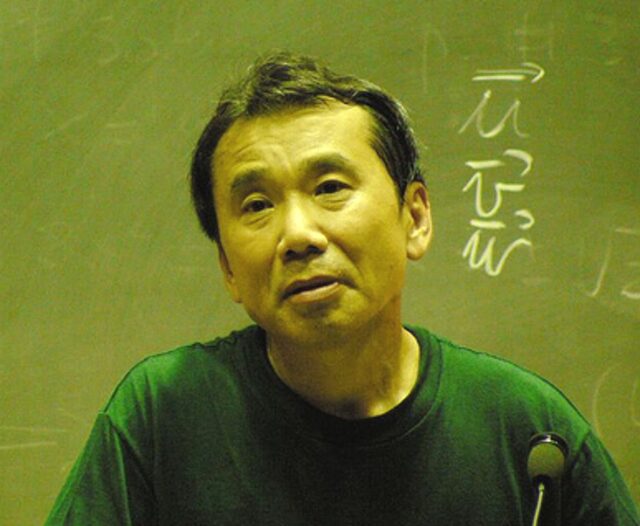

Haruki Murakami is one of the most prolific contemporary writers, and for good reason. His often-bizarre novels and short stories have been globally recognized. The English translation of his latest novel, The City and its Uncertain Walls, was released in November. It began as a project to rework an old short story from the 80s that Murakami wasn’t satisfied with and now stands as a magical realist story veering between retrospection and fantasy.

A cornerstone of Murakami’s work is his magical realism, a genre that originated in Latin American, notably popularised by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Magical realism differs from fantasy by presenting surrealist elements as completely normal within their settings. In The City and its Uncertain Walls (2024), this manifests in the perpetual youth of a girl and an uncanny walled city. Murakami’s magical realism has garnered critical acclaim; he won the World Fantasy Award for Kafka on the Shore (2006). A common theme in both works is escapism. The City’s protagonist escapes the static, unchanging city into the unfamiliarity of the isolated Fukushima province. Kafka on the Shore describes a boy’s journey to escape his perverse desires. The latter was in fact so laden with complexity that Murakami allowed readers to send him questions about it and answered many of them.

Through all the complexity and differences in his body of work, one key idea rests at the heart of each story: isolation. His protagonists are characterised by their deep introspection and desires to escape from the world, and each new character is set apart from the rest. Each human being in a Murakami novel exists in a system of their own thoughts and environments, and this is never clearer than in Norwegian Wood (1987)- my personal favourite, despite its lack of fantastical elements.

Through all the complexity and differences in his body of work, one key idea rests at the heart of each story: isolation.

Norwegian Wood takes its name from the song by the Beatles, that is mentioned throughout the book as a retrospective tool. Murakami’s novel follows a university student named Toru, who bears striking biographical similarities to Murakami himself. Toru’s best friend commits suicide, and he becomes obsessed with his friend’s girlfriend, Naoko. This love is fraught with misunderstandings, and despite their undeniable intimacy, there exists an impenetrable barrier between them. Grief permeates the novel, magnifying Toru’s feeling of loneliness as the narrative develops. What still captivates me about Norwegian Wood – despite reading it three years ago – is the universality of Toru’s aloneness, which Murakami describes with characteristic eloquence. The profundity of his grief and his inability to understand his friend’s suicide demonstrates his isolation, through which Murakami deftly reveals the intrinsic human desire for connection.

The profundity of his grief and his inability to understand his friend’s suicide demonstrates his isolation, through which Murakami deftly reveals the intrinsic human desire for connection.

Haruki Murakami is a writer renowned for many things, but the most resonant part of his work will always be his portrayal of human loneliness. And, paradoxically, through reading about all these absurd and lonely people, you get to feel a little less alone yourself.