It’s no use being told that there’s ‘plenty more fish in the sea’ when all those potential love interests seem to be swimming away as fast as they can. Not so for these flirtatious fauna, however, who have certainly got the skills where it counts – if you’re feeling lonely around this Valentine’s Day, perhaps now is the time to start taking notes.

Great Bowerbird, Chlamedyra nuchalis.

.jpg)

Image: Wiki Commons

Despite the bowerbird’s genus, Chlamedyra, sounding more likely to prompt a hasty trip to the clinic, the males of this species have still got a trick or two up their feathery sleeves. These Australian residents are named for their elaborately woven bower structures, which they build to impress the females – a little like an oddly sexually-charged episode of Grand Designs. The male birds adorn their bowers with rocks, bottle caps, and other such curios, and a recent study by one Prof. John Endler (Deakin University) revealed that the bowerbirds are proficient in using forced perspective optical illusions in order to make themselves seem larger and more attractive.

I can think of one or two uses for forced perspective in human flirtation, but I won’t go into detail here – I’m sure it’ll come to you, if you just think about it long and hard…

Giant Cuttlefish, Sepia apama.

Image: Flicker.com

Whilst cuttlefish sex is pretty odd – utilising the sort of weird face-enveloping techniques usually relegated to the darkest corners of Timepiece – their courtship can be pretty incredible. Cuttlefish can change colour to suit their surroundings, which comes in handy during mating season when competition is fierce – males seek to impress females and scare off rivals using vibrant colour-changing displays. Female cuttlefish are not averse to having multiple partners (try before you buy, that’s what I always say), so the lucky male will stand guard. Other smaller males have learned to get around this by changing their colours to pose as females, enabling the female to get some on the side, whilst presumably giving the first male an unexpected chance to explore his sexuality.

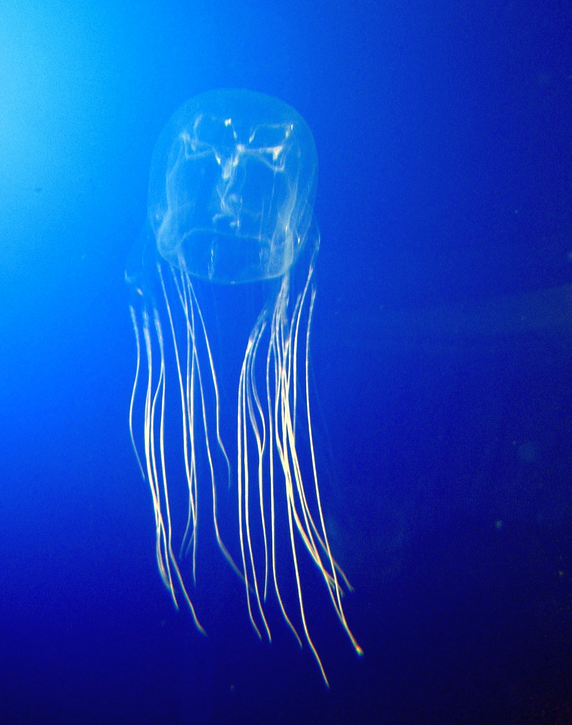

Box Jellyfish, Copula sivickisi.

Image: Wiki Commons

The box jellyfish, it seems, is really into oral sex. Not that it has much choice – jellyfish, as a rule, have just the one orifice: the opening of the central ‘manubrium’ tube functions as both anus and mouth. Tasty. Most jellyfish avoid sex altogether, simply releasing their sperm and eggs into the water and hoping for the best, however the box jellyfish decided somewhere along the evolutionary ladder that it was time to get kinky. When they gather for the customarily weird jellyfish orgy, the male jellyfish manually transfers a package of sperm to the mouth (or anus, personal preference I suppose) of the female, who then swallows (no comment), enabling a direct fertilisation. The male also coats his sperm cells with some of his stinging cynidote cells; these contain a protein used for anchoring on to targets, enabling the sperm to better stay attached to the female. So far, so vanilla – but then the female actually partially digests the sperm cells, allowing better bonding with her eggs. As I say – tasty.

Prairie Vole, Michrotus ochrogaster.

Image: flickr.com

Fear not, you hopeless romantics – love is not dead, and the prairie vole is here to prove it. Unlike most similar species, M. ochrogaster is typically monogamous, and remains so for life. Prairie vole couples engage in affectionate grooming, exhibit biparental behaviour, and (heartbreakingly – I never knew I’d get so invested in vole romance) most voles seem unable to move on after their loved one has passed away, exhibiting signs of loss-induced depression. The vole’s social bond is formed by long-term interaction between partners, and so many a vole’s one night stand has resulted in love. Aside from being undeniably adorable, the behaviour of the prairie vole has also presented an excellent opportunity for scientific research into the neural (and genetic) basis of mammalian social bonding. Personally, I just think it’s really cute.

Also here’s some vole-related science, because it’s kind of adorable.