Review: Cyrano

Despite finding something to love in its extravagance and flamboyancy, Clémence Smith argues that Joe Wright’s adaptation misses the point of its source material.

Cyrano seems like a promising film at first. It is a musical adaptation of the 1897 French play Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand and features a star-studded cast; needless to say, I was eagerly anticipating its release. Unfortunately, Cyrano left me bitterly disappointed.

The film’s strong points are undoubtedly its costume design and décor. Its varied colour palette triumphs on the big screen, echoing the hit Netflix series, Bridgerton. This initially flamboyant stage design gradually peters out as the plot darkens, which I thought was a nice touch. Nonetheless, you can’t put lipstick on a pig: delicately crafted visuals are not enough to cover up the film’s many pitfalls.

Let’s start by sketching some basic plot points. Cyrano, a cadet in the French army, is hopelessly in love with his childhood friend, Roxanne. She, however, is in love with Christian, who she meets by chance at the theatre. Despite his panache, Cyrano is convinced that Roxanne will never love him because of his dwarfism. Instead, Instead, Cyrano channels his love for Roxanne by helping Christian write letters to her. The story contrasts two types of men: Cyrano, on the one hand, who has wit but is not conventionally beautiful, and Christian, on the other hand, who is attractive but desperately inarticulate.

I was also astonished to see that one of the play’s most famous passages was completely cut out of the film

Joe Wright turns Cyrano, as The Guardian states, into a “letter ghostwriter”. I think that this is a gross oversimplification of Rostand’s original play. Cyrano is not merely about a love triangle – the original plot raises important questions about the discrepancies between inner self and appearance, which Wright dismisses in favour of a flippant romance.

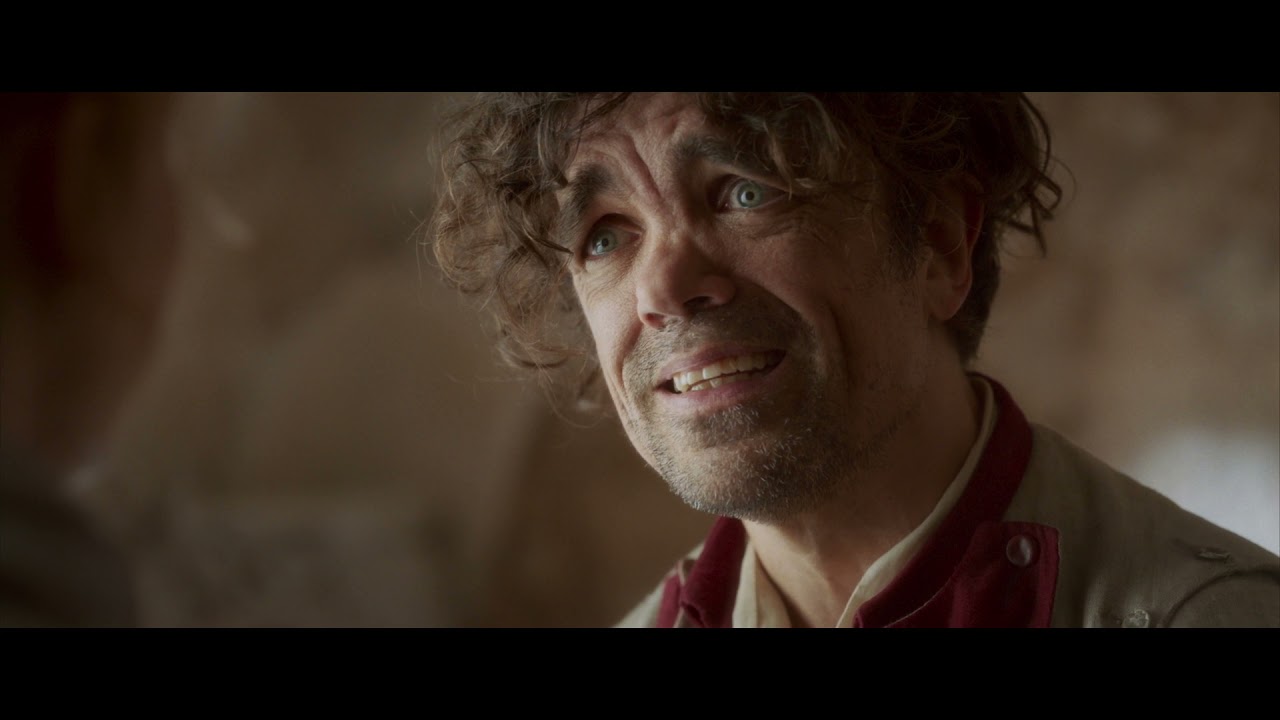

Furthermore, Peter Dinklage’s rendition of Cyrano is worlds away from Rostand’s eloquent and sharp-minded character. Dinklage stumbles in his speech and the various songs’ lyrics are far from awe-inspiring: rhyming Cyrano with “know” and Roxanne with “understand” is disappointingly shallow. In addition, Cyrano’s use of the word “Halloween” is a glaring anachronism, as the film is set in the 17th century, but the word only came into circulation in the mid-18th century. Wright’s attempts, such as these, at modernising the text are in my opinion cringe-inducing and, quite frankly, pointless.

I was also astonished to see that one of the play’s most famous passages was completely cut out of the film. Cyrano’s “no thank you” tirade is a crucial moment in Rostand’s text, as it establishes Cyrano’s commitment to freedom of speech. It also highlights his rhetorical skills, as he spontaneously and effortlessly crafts a compelling argument that condemns the corruption of the ruling class. Removing this scene further trivialises Cyrano and the social reforms he champions.

Last, but certainly not least, the actors’ singing is underwhelming and Dinklage in particular struggles, painfully, through his melodies. Ironically, Kelvin Harrison Jr., who plays Christian, exhibits more verbal prowess, despite supposedly lacking it. After Roxanne’s lead number “I need more”, I was left, like the song’s title, with little hope for the film’s second half. The songs felt mechanical and insincere and honestly made me want to laugh instead of cry during the film’s rawest moments.

In short, I would urge you to read Rostand’s play instead of watching Cyrano. Although I admire Wright’s ambition, his adaptation crumbles under its own weight. Modernisation need not go hand-in-hand with oversimplification: if anything, a good adaptation should develop its source rather than gloss over the issues it raises.