A beginner’s guide to comets

Almudena Visser Velez explains the phenomenon of comets appearing in our solar system.

In news articles in recent weeks, some readers may have seen photos of what looks like a green smudge on a dark background, or perhaps even seen a bright object in the sky, but what were they?

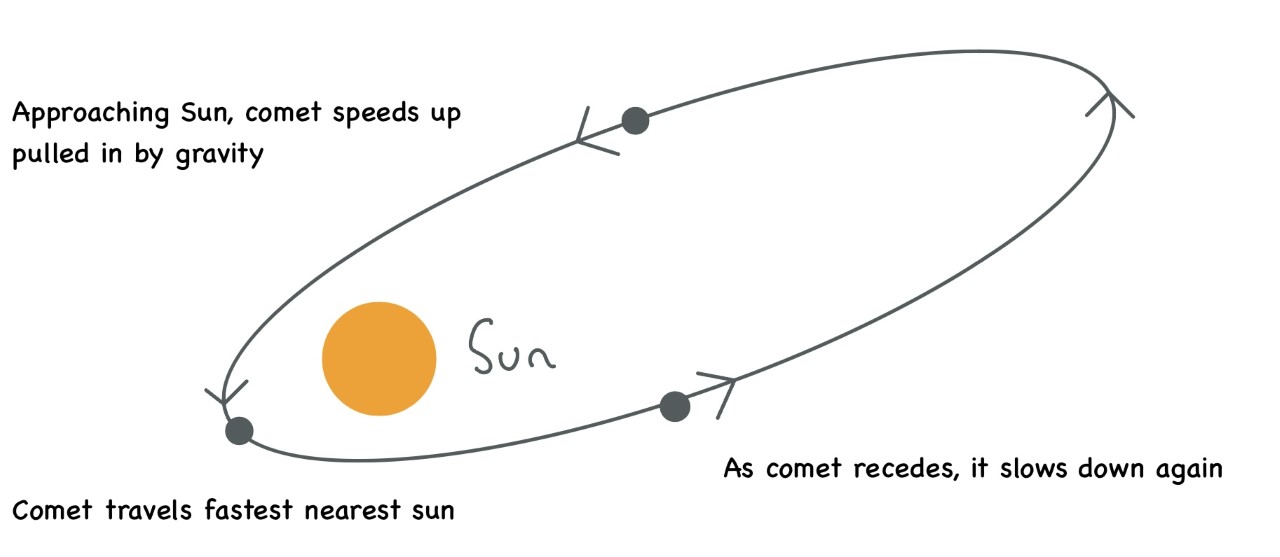

Comets are frozen objects composed of dust and ice that orbit the Sun, or a less flattering description would be enormous, dirty snowballs. Their orbits are usually elliptical and they may come from very far away, outside our own solar system, melting and burning up if they come too close to the Sun. Comets travel at thousands of kilometres per hour, with speeds exceeding 100,000km/h as they approach the Sun and get pulled in by its gravity. Comets with shorter orbital periods may orbit the Sun several times, while those with longer orbits may only ever come around a single time, so seeing one may truly be a once in a lifetime experience.

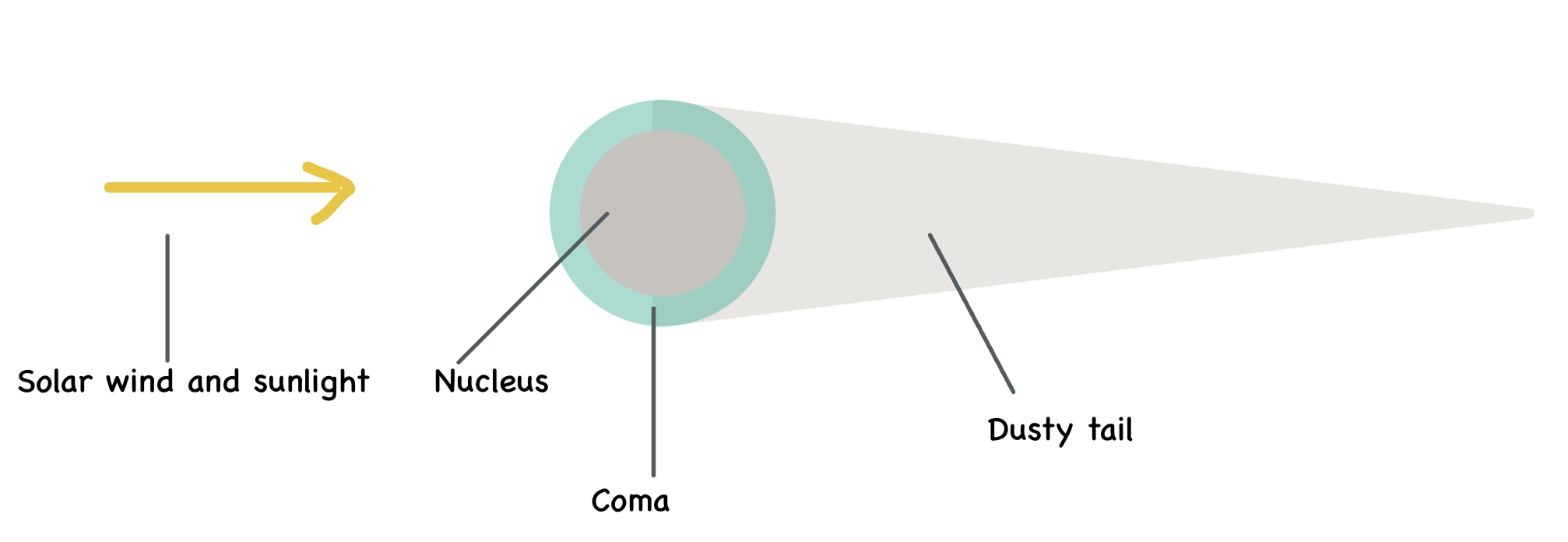

They consist of a frozen core, called the nucleus, which can be around 10 km wide. As the comet approaches the Sun, it heats up and the ice sublimates to a gas, causing a fuzzy cloud to envelope the nucleus, called a coma. As the dusty gas streams off the nucleus, solar wind pushes the gas into a line behind the core, causing the famous bright trails that can run for millions of kilometres.

The comet that has hit the headlines recently is called C/2022 E3 ZTF. It swept through the sky in January and was closest to Earth on February 1st (coincidentally this author’s birthday). In long exposure telescopic photos, it came up as a bright green haze and could be seen through binoculars and potentially sharp eyes away from light pollution. This comet comes near Earth every 50,000 years so was last visible in the Stone Age, meaning you might have witnessed the same spectacle as some very distant ancestors from a long bygone era – an extraordinary thought. As the comet is now receding from Earth, it will become harder to see and will soon disappear from view.

The bright green colour of the main body, not unique to this comet, is thought to be caused by sunlight interacting with diatomic carbon, an unstable gaseous form of carbon with paired atoms. The dicarbon molecules are broken down by extreme ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, releasing energy in the form of light and causing a green glow, after which they split into single carbon atoms which form the coma.

The picture linked here, composed of three images, illustrates how using visual tools can help us see the comet more clearly. The main image, taken in western Spain at the end of January, shows it to be just about visible to the unaided eye. The comet can be distinguished from background stars by the faint smudge of light trailing behind. The top inset shows the comet through binoculars in more detail, while the sharpest image was taken with a small amateur telescope, revealing C/2022 E3 ZTF in all its glory.