Trigger Warning: Mentions of suicide and gender dysphoria.

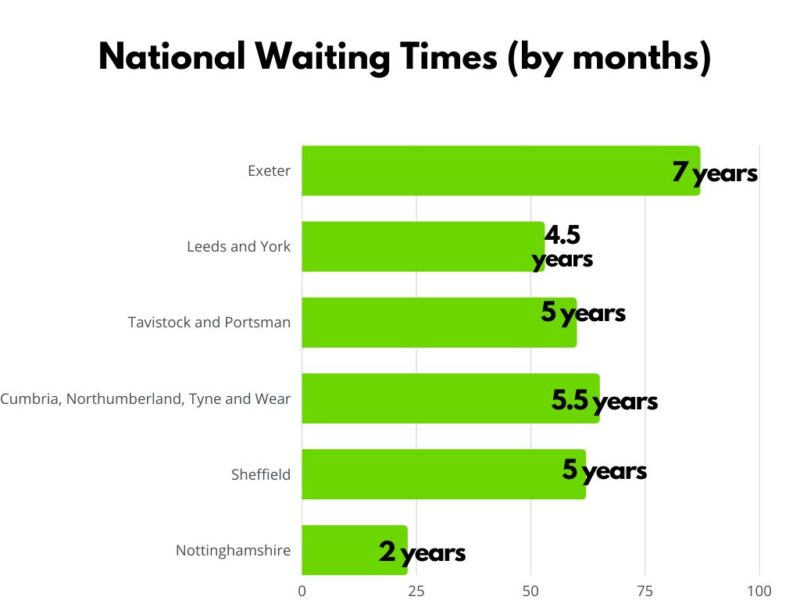

University students throughout the country describe extremely long, inconsistent, and inaccessible waiting times for receiving gender-affirming care. In an inquest made by Exeposé of all NHS-supported Gender Dysphoria Clinics in England, a total of 16,649 individuals aged 18-25 are on the waiting list and in need of gender-affirming care. This number encompasses a wide number of University students who find an inability to alleviate the consistent hardships that come from gender dysphoria.

In Exeter alone, the Laurels – Exeter’s Gender Identity Clinic – estimates a seven-year waiting time despite hundreds of individuals joining the waiting list each month. On that waiting list, an FOI depicts over half (53.71%) to be clients aged 18-25 as of August. At the same time, over half of the referrals (55.10%) are within the same age cohort. Only 30.11% of that age range are receiving care and even fewer (23.81%) have completed their treatment. All the while, waiting times are reportedly on the rise.

On that waiting list, an FOI depicts over half (53.71%) to be clients aged 18-25 as of August. At the same time, over half of the referrals (55.10%) are within the same age cohort. Only 30.11% of that age range are receiving care and even fewer (23.81%) have completed their treatment.

These waiting times are said to perpetuate gender dysphoria and heighten suicide ideation and suicide attempts. This has been unfortunately proven true most recently with the widespread coverage of 20-year-old Alice Litman’s death, who took her own life whilst waiting for gender-affirming care. A written statement to an inquest by Dr Caroline Litman, an NHS psychiatrist, as well as Alice’s mother, said: “We believe that Alice died partly because of the inaccessibility of gender-affirming healthcare in the UK.” She adds “I believe my daughter could have lived a happy and healthy life had she not been failed by the healthcare system that should have supported her.”

University students across the country are remarking similar debilitating well-being concerns. In a Journo Request released nationally by Exeposé, a student on the Leeds Gender Identity Clinic Service describes that they are within their tenth month of an estimated four-and-a-half-year waiting time. Another has been waiting four years for a first appointment through Devon’s service. They write that “private gender-affirming care is very expensive” which is why they chose to go through the NHS. “It is certainly good that this care exists in England,” the anonymous student writes, “however, the wait times are extremely disheartening.”

Another student, who has been on the waiting list for four years at the Tavistock and Portman location in London, mentions “wanting to go private due to the long waiting times and distress caused”, but being unable to afford private fees.

In the Summer of 2021, an unnamed student at the University of Exeter began taking the steps for their own gender-affirming care. Due to the prolonged waiting time that was affecting their mental health, they switched to private as they had access to private healthcare. Whilst the process sped up, their bills skyrocketed as they had to pay £1110 for treatment. Even with the ability to pay, they discuss being “unable to receive care for months as there is still a lack of medical practitioners specialising in gender dysphoria.” There is only one practising around Exeter.

In a Journo Request released nationally by Exeposé, a student on the Leeds Gender Identity Clinic Service describes that they are within their tenth month of an estimated four-and-a-half-year waiting time.

The overarching narrative from students illustrates limited care options for those needing gender-affirming care from working-class backgrounds as individuals could wait for ten years for one appointment with the debilitating experiences of gender dysphoria. They are barred from private services, lest they save up money which–intermixed with the symptoms of gender dysphoria and general length that accumulates from trying to save up thousands of pounds–is a mountainous endeavour.

For students where receiving private care is possible, they still report having to work to afford endocrinologist appointments and hormone medications. One student who had private access had enough money to afford living expenses so that all their working money could go towards their gender identity healthcare. The student describes the impacts this had on their mental and physical health in which they were “consistently stressed” and facing the challenges that are involved with gender dysphoria. For those who must support their own costs of living in addition to gender-affirming care, precarious day-to-day living is expected. Another student on private care whilst attending the University reports estimated costs of “at least £2000 a year” when they were using the Gender GP service (which is lauded as one of the most affordable options for private gender health care). This student source explains that “the estimation comes from when I added up startup fee, monthly subscription, the required follow-up sessions and medication costs in addition to some other procedures I felt I needed to pursue.”

Another student speaks of choosing private as they explain, “The waiting lists were a decade long and I wouldn’t have managed to keep myself alive for that long.”

Students who do join the waiting list during their time at the University are unlikely to receive care until after they graduate.

Following their own research on waiting times, another student says they “didn’t even want to bother” with spending time on the waiting list as they felt they needed care right away. This decision “definitely had an effect on their living costs.” They tell Exeposé to “bear in mind that after my tuition fees, my master’s loan left me with £4K and my healthcare ate through a quarter of that.” They explain having to dive into their savings to “stay afloat.”

“I think it’s utterly unsustainable” the source continues, “Is it any wonder some of us don’t end up medically transitioning for years?”

Students who do join the waiting list during their time at the University are unlikely to receive care until after they graduate. When it comes to changing Gender Identity Clinics to accommodate their new locations after graduation, one may have to start the waiting time again depending on the clinic, though many, including Exeter, do not transfer care from any NHS waitlist.

Locally, the Laurels Gender Identity Clinic acknowledges the extreme waiting times. A spokesperson for the clinic tells Exeposé: “Our team is passionate about supporting people with gender-related needs and we know how stressful long waiting times can be. This is a problem seen across the country, created by a steep rise in demand in recent years.”

Paul Stemman, a press officer for the clinic, states “We hope some changes will be made, but that hasn’t come through yet.” When asked if the clinic has anything specifically in place to support students, Stemman says “[the clinic] has done training with the Uni Wellbeing Team in the past and also with students on certain courses in Plymouth. However, there is nothing systemic in place.” When it comes to changing addresses, the clinic reports that “there’s nothing to support students if they move areas after graduating.”

Students at Exeter express a want for University intervention.

Students at Exeter express a want for University intervention. A lack of accessible services that explain, recommend, and guide students on dealing with gender dysphoria is not as robust as other universities. The University of Birmingham gives long-form guidance on supporting trans staff and students; the University of Sheffield is equipped with definitions of gender dysphoria. Signposting to specific lines of support could help get steps in place for those who do not know where to start with their care. Ways to mitigate financial distress by way of the Student Success Fund are already in place by the University – though there is a lack of publicity that it can be used for gender-affirming care, according to Exeter’s LGBTQ+ society.

The Students’ Guild comments “We want to create an environment on campus where everyone feels they belong, and we encourage students to connect with our LGBTQ+ community for peer support or reach out to the University’s Wellbeing Services. Whilst we don’t work with [the] Gender Identity Clinic, we are working with students to create a Gender Expression Fund (GEF) which we expect to launch in mid-October.”

The GEF fund is a student-led idea and is being co-designed with students, and funded by the Guild. The fund is expected to support trans and non-binary students who may need additional funding support whilst at the University.

“We’re by far not the first Gender Expression Fund in the country”, says Hallow Foster, one of the members of the Gender Expression Fund Team. “UCL, Cambridge, and Bournemouth all have their own versions. However, we are the first trans-specific help at this University.”

They say “We strongly believe that no one should have to pay to be who they truly are. We’re setting this fund up to allow trans, non-binary, and gender non-conforming students to buy the necessary items without choosing between their mental and physical health and safety and paying their bills.”

By helping to establish the fund, the Guild is trying to show that Exeter is a safe place for trans people. “It’s trying to show that we are welcome here and that they’ll do what they can to help us” says Foster.

“If I’m being honest, the continued survival of the fund will rely on students heading the team. It relies on enough students using the fund that the Guild says is worth it. I do think that the Guild will fight for its continuation, but that uncertainty is a bit scary for those who are helping create it” says a member of the LGTBQ+ Society.

Some students who have heard of the fund are happy; yet, worried that it won’t remain for that long. “If I’m being honest, the continued survival of the fund will rely on students heading the team. It relies on enough students using the fund that the Guild says is worth it. I do think that the Guild will fight for its continuation, but that uncertainty is a bit scary for those who are helping create it” says a member of the LGTBQ+ Society.

Students believe that Student Unions are monumental in being able to bring these modes of support to fruition. Universities also have tremendous sway in maintaining them and offering further monetary support for them to stay.

In the future, students from across the country hope to see solid University support in the form of Gender Expression Funds or actively campaigning for trans and non-binary student support.

For more reporting on waiting times for trans and non-binary students visit this article in Exeposé news.