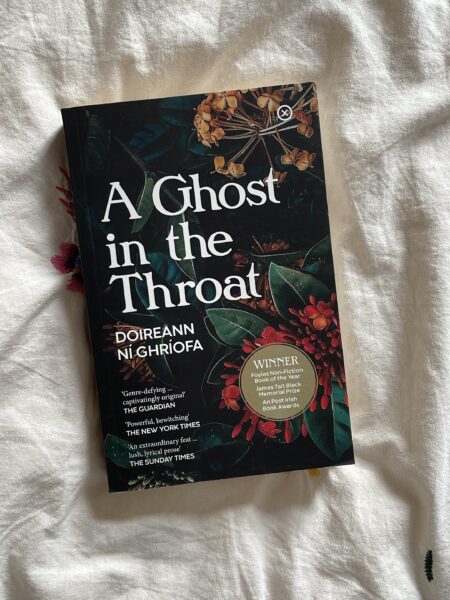

As a fan of the morbid and unsettling, I’ve frequently been drawn to certain works of Irish writers. With short story collections such as Niamh Mulvey’s Hearts and Bones: Love Songs for Late Youth and Moira Fowley’s Eyes Guts Throat Bones and books such as Doireann Ni Ghriofa’s A Ghost in the Throat, even the titles take on an undeniable motif: bodily imagery. This is carried throughout the works themselves, with stories of deconstructed bodies, cannibalism, and the supernatural making up a considerable portion.

A Ghost in the Throat is a piece of autofiction, following the life of a young mother in parallel with her own obsession: “Caoineadh Airt Ui Laoghaire”, a poem by 18th century writer Eibhlin Dubh Ni Chonaill. This poem paints an image of the grieving narrator, mourning at the body of her husband and drinking his blood: “Love, your blood was spilling in cascades, / and I couldn’t wipe it away, couldn’t clean it up, no, / no, my palms turned cups and oh, I gulped.” This act of body consuming body epitomises the harsh physicality of the text, tied closely to the physical experience of the young mother. One passage on motherhood discusses the effect of pregnancy on a woman’s body: “If she cannot consume sufficient calcium, for example, that mineral will rise up from deep within her bones and donate itself to her infant on her behalf”. Once again, we can observe a body consumed – this time, by itself. Ultimately a documentation of female experience – it is a self-proclaimed “female text” after all – this book expresses the visceral and profound aspects of womanhood and motherhood across centuries.

Although taking on the structure of shorter form content, Eyes Guts Throat Bones maintains this level of morbidity, whilst introducing the mystical and miraculous, from physical impossibilities such as humans morphing into animals to ancient female forces living on under the earth. These stories experiment with extended metaphor; while they remain consumed in physicality, they express something beyond. One story – “Such a Pretty Face” – is written from the perspective of a woman who steals her lovers’ faces before moving on, taking on their identity until finally she meets someone who understands what it is she is doing. Another, titled “Rath”, blends two stories – one of two friends who meet at the same place each year for decades, engaging – only on that night – in intimacy, with that of an ancient female spirit living under the earth where they meet. Similarly to A Ghost in the Throat, this combination of stories new and old expresses a unity in female experience, and in the case of Fowley’s work, queer female experience.

this combination of stories new and old expresses a unity in female experience, and in the case of Fowley’s work, queer female experience

Hearts and Bones: Love Songs for Late Youth doesn’t engage quite so brutally with the body, but unsettles through other means. “The Doll” details the relationship between a boy and his ventriloquist doll, who speaks to him savagely: a representation of his own self-image and worldview. The destruction this relationship reaps on his life is made viscerally disturbing through the presence of the doll, which “need[s] more blood” and tells him that his girlfriend “was never going to stick with [him].” This story uses the disturbing image of an animated doll to communicate a complex relationship with the self, rendering the unsettling a useful tool.

While these stories take on a commonly explored theme, they do so with a unique effectiveness. Perhaps it is the country’s history – that which coloured the works of James Joyce and remains impactful today – or simply the country’s cultural perspective that draws these stories from the body and from the earth. For anyone interested in the macabre and tired of English or American ghost stories, Irish works can be an interesting and delightfully disturbing endeavour.