Art and science share a deep connection. Both take on the profoundly human endeavour to explore and understand the world around us – and share this understanding. These two disciplines have been in dynamic exchange with one another for years; there is an art to science and a science to art. They have the same sole foundation composed of observation and interpretation. That is why artists have found such great inspiration in scientific discoveries throughout history for their artwork to demonstrate the human’s search for answers and order.

The Renaissance polymath Leonardo DaVinci and Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens offered remarkable insight into human anatomy in their anatomical drawings. These scientific strivings in anatomy made waves in the art world, yet science’s interweaving into art does not stop here.

These two disciplines have been in dynamic exchange with one another for years; there is an art to science and a science to art.

This article will outline a collection of paintings exemplifying the use of art to illuminate the fascinating beauty of science.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632) — Rembrandt

Rembrandt’s Baroque oil painting pertains a common anatomy lesson in the 17th century, illustrating Nicolaes Tulp explaining the muscles of the arm to a group of doctors.

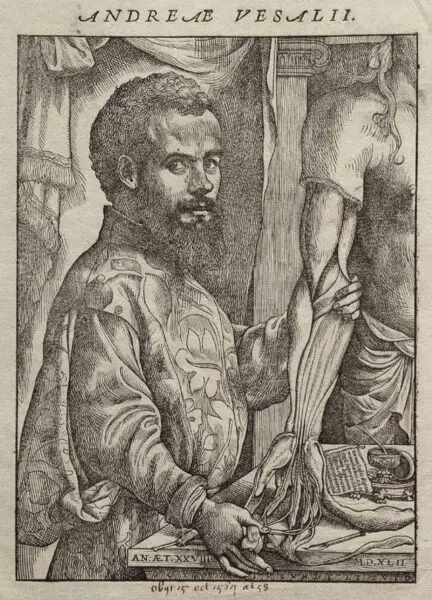

This painting altered the conventions of the anatomical genre by featuring the full body of a corpse. The figure, laid and dressed in a white cloth, emulates images of Christ, likened to portrayals of Jesus laid out after his crucifixion. Rembrandt’s striking, stylised positioning and expressions of the doctors around the male cadaver creates a dramatic mis-en-scène. Rembrandt utilises the light coming from the left to create partial shadows on the corpse’s face to extenuate the umbra mortis (otherwise known as “the shadow of death”) on the corpse’s face. While Rembrandt is able to capture such a brutally grotesque scene, experts have commented on the inaccuracies of the left hand of the corpse. The anatomy is indubitably wrong. The corpse is painted with two right hands! This has generated great intrigue because over one hundred years, in the sixteenth century, before Rembrandt painted The Anatomy Lesson, Andreas Vesalius, a renaissance anatomist, wrote De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. This book included a woodcut portrait depicting an anatomically accurate right hand. It has even been postulated that the book in the bottom right corner of the painting is Vesalius’s book containing this portrait with the detail of a dissected upper extremity. So why did Rembrandt make such a blatant and flagrant mistake? This question of why Rembrandt would have detailed such discrepancies remains unanswered and fuels the fascination of historians and scientists alike with this painting.

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768) — Joseph Wright of Derby

This candlelit scene, painted during the Age of Enlightenment, captures the intense drama of a scientific experiment including a living animal. The painting functions as a “vanitas” enthused with the theme of the passing of time, the limits of human knowledge and the fragility of life. The scene presents a scientist demonstrating how sucking air out of a Boyle pump creates a vacuum, ergo, how a bird cannot breathe inside the jar without oxygen. The tensions between scientific and religious conceptions of emptiness are evoked. Tenebrism, derived from tenebroso, an Italian word meaning “dark, murky, gloomy,” is used to create dramatic contrasts between light and dark. While tenebrism developed from chiaroscuro, unlike that technique, it did not strive for greater three-dimensionality but was compositionally used to accentuate that the oil painting’s dark areas of negative space and deep shadows, intensely illuminated, by a single light source. Wright illustrates a plethora of reactions to the experiment. Those of which include curiosity, inquisitiveness, concern, guilt, despair, fear. The painting is poignant display of the breadth and depth of the human emotion spectrum. the ephemerality of time and transience of time is the message that cuts through.

The Alchemist (1771) – Joseph Wright of Derby

The grandeur of the Renaissance was mirrored by its equally sublime style of artwork, out from which evolutions in drama and depth were innovatively conveyed. The era’s artists accomplished this through new techniques centered upon the manipulation of light and dark, the father of which was chiaroscuro. Combining two Italian words – chiaro, “light” or “clear,” and scuro, “dark” or “obscure,” it became an artistic method using gradations of light and shadow to create convincing three-dimensional scenes where figures and objects appeared as solid forms. The Alchemist demonstrates the notorious experiment that lead to the discovery of phosphorus by the Hamburg alchemist Hennig Brand in 1669. Brand was attempting to discover the Philosopher’s Stone that could turn base metals into gold. He attempted this by gently evaporating a large quantity of his own urine until it was the same viscosity as honey. Instead, he made a waxy substance that glowed in the dark. Though it was not the desired product, phosphorus was discovered, an incredibly useful element that is a component in explosives and fertilisers. This painting is a romanticisation of this discovery. Wright does not picture the alchemist in a 17th-century background, but he dramatises this major scientific venture by reimagining the room with gothic, stone arches and high-pointed windows that resemble those of a church substantiating the contention between religion and science in the 1700s. Wright, further, uses light in his painting to foreshadow and reiterate the eighteenth-century as a juncture for change due to a shift from alchemy to chemistry. There are three light sources in The Alchemist: the moon, flame and phosphorus. This trinity of light sources, which can be likened to the “Holy Trinity”, each represent different sources of knowledge. First, the moon signifying nature, natural enquiry and inquisitiveness perhaps with a divine link. The flame perhaps mirrors the mind and spirit, spiritual reason and intuition. The final source of light is phosphorus, this is the artificial, scientific symbol of knowledge and infers scientific optimism. The latter’s light has an overwhelming intensity in the painting, revealing how the Enlightenment of man is beginning to reign supreme over religious absolutism. The colouring of the phosphorus light source has a slight blue hue and touches all reflective surfaces in the room. Wright instead of scraping the surface paint to depict the phosphorus’s light, Wright instead places a dab of white paint on top of the existing layers. Such a technique can be read to indicate that the phosphorescent light is a dominating, external and unnatural presence as it spreads through the room.

The painting overall can be interpreted to establish the light of rational science triumphing over religious superstition, the vindication of chemistry from its alchemical past and/or the glory of human scientific and rational procedure.

“The Persistence of Memory” (1931) and “Metamorphosis of Narcissus” (1937) – Salvador Dalí

The infamous surrealist, Salvador Dalí, draws inspiration from Einstein to explore time in his instantly recognisable masterpiece. The iconic melting clocks have been theorised to be prompted by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, which transformed our understanding of time and space. Dalí’s depiction of time as fluid, distorted and malleable resemble Einstein’s proposal of time and space not being fixed. The painting, as does Einstein’s revolutionary theory, invites viewers to question the fixed notions of reality. Dalí was also fascinated by the concept of the fourth dimension. He translated the theory into his work through the use of optical illusions.

Dalí was not only fascinated by physics. Biology and the human mind piqued his interest, and he referenced the psychoanalytical work of Sigmund Freud in his painting “Metamorphosis of Narcissus”. Dalí depicts the mythological figure Narcissus, who was self-absorbed and obsessed with his handsome reflection. Dalí’s interprets the myth to show the transformation of Narcissus into a flower. He paints a hand holding an egg, a symbol of rebirth and potential. This image is reflected in the background as a landscape, which resembles a human head and suggests the idea of the unconscious mind. Dalí described that reading of Interpretation of Dreams was one of the “capital discoveries” of his life.

Dalí was also fascinated by the concept of the fourth dimension. He translated the theory into his work through the use of optical illusions.

Freud’s ideas about the unconscious fascinated Dalí and he believed that art could be a tool to explore the depths of the human psyche.

Both scientists and artists aim to express something new about the world from new angles and then communicate their visions. In their success, our ways of “seeing” and our concept of “truth” is changed.

Art and science have an incessant hunger to make sense of things. As humans we are terrified of the unknown and senselessness. We crave order. And while, art and science may not always offer this, they are the tools for discovery and progress. They should not be treated as separate spheres, but intertwining disciplines that inform how we view the world, that can buttress and nurture one another.