Excess Food Consumption: Food Art Over the Ages

Emma Blackmore analyses the use of food symbolism in art to criticise human overconsumption.

Artistic representations of food are linked to the discourse of production and consumption, waste, and luxury. From Vincent Van Gogh and Pieter Bruegel to Edward Hopper and Andy Warhol, depictions of food have spanned across centuries. The fascination with food in art reveals a myriad of human experiences and relates not to just feasting and fasting, but giving thanks and conveying an opinion.

The fascination with food in art can be traced back to ancient Egypt. Food drawings can be seen within the inner walls of the burial chambers in the Pyramids and it was believed that they contained magical properties that would nourish the afterlife. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, portraits of banquets would emphasise wealth and exoticism, while depicting a moral purpose. Between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, still-life paintings as a genre flourished. By the end of the nineteenth century, food quickly became associated with realism and the changing nature of society.

Diachronically tracing overconsumption from the seventeenth century to the twenty-first century reveals an increasing uneasiness with the excess of consumption and food waste. Art serves a political purpose, as well as a moral one, and paintings of food are no exception.

In Andries Benedetti’s A Pronk Still Life with Fruit, Oysters, and Lobsters, (c. 1640–1645) the Flemish painter shows off his technical mastery within his lavish display of exotic wealth. Enormous bright red lobsters are laid haphazardly on a pewter bowl, surrounded by an abundance of fresh lemons and green grapes. The stark white linen thrown over the chair, and in the middle of the painting, brings out the white of the oysters and their extravagance. Orderly nature and excess consumption are juxtaposed at the right of the painting with the end of the white linen drawing the eye down to the elaborate navy vase on its side. The disorderly amalgamation of not only lobsters, grapes, and oysters, but of colour, linen, and household items, reveals a satirical glimpse into an excessive feast fit for a king.

Art serves a political purpose, as well as a moral one, and paintings of food are no exception.

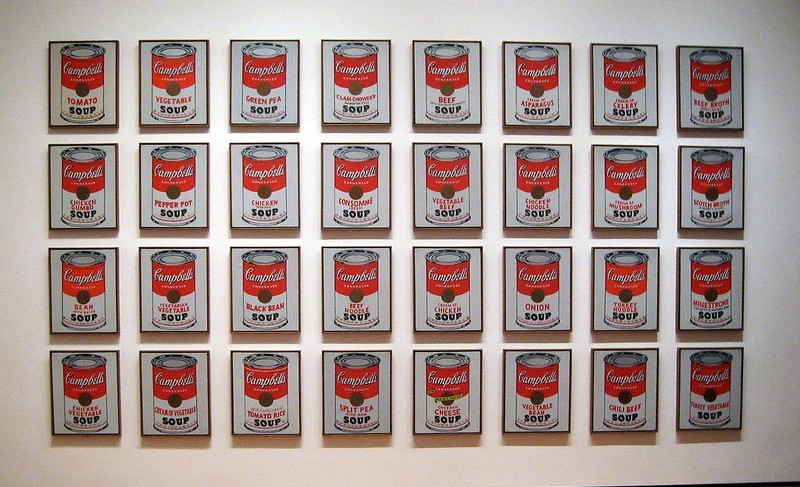

Three hundred and seventeen years later, Andy Warhol satirised overproduction and overconsumption in his 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans paintings (1962). Alongside the uniformity of the products, Warhol appropriated familiar adverts from consumer culture and mass media to highlight 1960s homogenising mass culture. With thirty-two variations of soup, the canvases are lined next to each other in rows of eight, further emphasising the image of visiting the supermarket. The canvas emphasises the plethora of choices available. However, compared to Benedetti’s still-life, the quality and freshness of food has deteriorated. Warhol highlights the decline in traditions, such as eating around the table and eating fresh, due to twentieth-century mass-produced culture.

The Korean artist Nanda’s The Coffee Bean (2008) is a fascinating exploration of consumer culture and excess. Nanda’s painting illustrates traditional Korean culture with a disposable coffee mug from the Coffee Bean, an international coffee chain. Nanda juxtaposes a traditional tea ceremony with disposable coffee cups and women dressing the same, seemingly like a mirror, even down to their sunglasses. Evoking Warhol, Nanda criticises mass-produced food and the effects of waste. Strikingly, Nanda’s homogenous experience in The Coffee Bean with its emphasis on one-use cups channels the discourses occurring on Instagram relating to food waste, food excess, and food art.

The last ten years have seen a growth of measures to tackle overproduction and waste. Although there is much more to be done, Instagram seems determined to be the next medium to embrace, criticise and politicise food — one Costa Coffee cup at a time.