There was a time when the single most important fiscal event in the political calendar was the unveiling of the government’s budget. It was the chance to tell the public what the economic forecast was, and what kind of path the government would be charting through it. Nowadays, there is an additional important event worth considering: the Autumn statement.

In the weeks preceding its unveiling on 22nd November, there was endless media speculation about what might appear in the Autumn statement. Briefings threw doubt on whether the triple-lock would be upheld, which sees annual rises in the state pension, and there were hints of possible cuts to inheritance tax. In the end, both saw no changes.

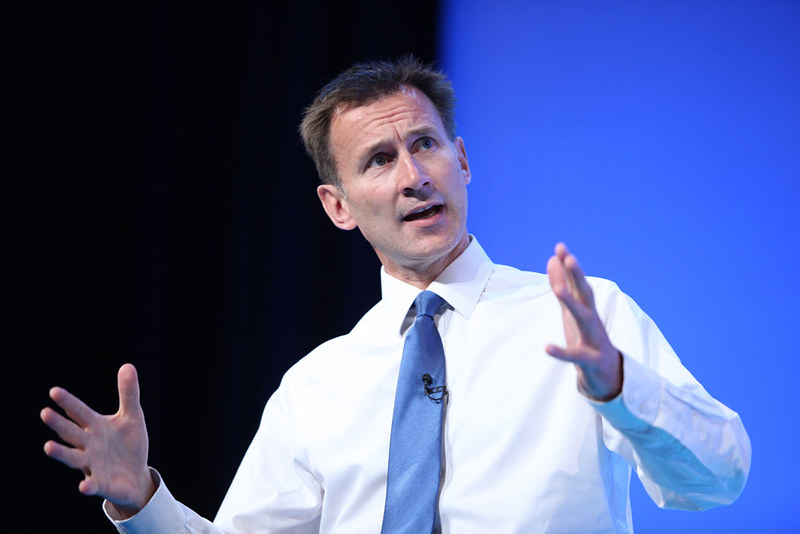

Perhaps the most important question was how any new cuts or potential spending were going to be paid for, as it was only a few months ago that Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt said that tax cuts would be “virtually impossible” in the current economic situation.

When the statement appeared on Wednesday, the reaction to it came with two primary and competing headlines: either ‘highest tax burden in decades,’ or ‘largest tax cut in a generation.’ According to the Chancellor, it is actually both, and whilst he is technically correct, this doesn’t paint the full picture.

Although they have long been thought of as the party of low tax, after 13 years in charge, the Conservatives are now overseeing what the Institute for Fiscal Studies is judging to be the biggest tax raising parliament in the post-war period. On top of this, the decision to freeze income tax thresholds for the past four years has caused ‘fiscal drag’, as inflation has meant that more earners have been pushed into higher tax brackets, and are thus paying more. This gave the treasury some flexibility, and it is what precipitated this statement.

Although they have long been thought of as the party of low tax, after 13 years in charge, the Conservatives are now overseeing what the Institute for Fiscal Studies is judging to be the biggest tax raising parliament in the post-war period.

This chance has been used for a tax cut, as it has seen a reduction in National Insurance (NI) rates. This means that the initial contribution, for those earning above £12,570 and must pay NI, will drop from 12 per cent to 10 per cent. Changes like these are likely to play well to the base of the party membership which has been calling for this kind of cut for a long time. With a general election on the horizon, that is shaping up to be a wipeout for the Conservatives, many are accusing the government of acting in the interest of their polls and not the country’s economic health, but Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has denied this by pointing out that this is just a benefit of his role in reducing inflation.

To meet the rising cost of living, another change will see a rise in the minimum wages, which is especially meant to benefit young workers and low-income households. In April the National Living Wage and the National Minimum Wage will both see rises. The former will rise from £10.42 an hour to £11.44 an hour for over-23s, and for the first time, 21-22 years olds will also be eligible to earn the same. The latter will see 18–20-year-olds now earning a minimum of £8.60 an hour, up by £1.11, and under-18s earning a minimum of £6.40 an hour, up by £1.12.

At the same time, universal credit will also see an increase by 6.7 per cent, to meet inflation, plus extra funding, totalling £2.6 billion, will be made available to help people find work if they have been unemployed for over a year, or if they have health issues that make finding jobs difficult. Other benefit changes have prompted some concerns however, as if claimants do not end up employed then they risk losing access to said benefits.

This isn’t the only potential downside, as projections suggest there may be more gloom ahead. Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that GDP growth has grinded to a halt in 2023, and what amount to minor tax changes will likely do little to change that. The Office for Budget Responsibility has also recently said that the economy will not be expected to reach more than above 1 per cent growth until 2025, meaning that living standards won’t even return to a pre-pandemic level until 2027, despite the Autumn statement. These struggles can similarly be seen throughout the rest of Europe as high interest rates persist even as high inflation has finally begun to fall.

Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that GDP growth has grinded to a halt in 2023, and what amount to minor tax changes will likely do little to change that.

Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves used the statement as an opportunity to broadcast Labour’s alternative vision for the country, particularly targeting the Conservatives on their failure to bring in extra tax revenue from those with non-dom status and their overall record on the economy after so many years in power. But it is also worth pointing out that, despite her disagreements, Reeves has made the same commitments to cutting NI and keeping the triple-lock for pensions.

This is perhaps what reflects the general state of the UK economy the most. Low growth means few options, and a lack of solutions means more discontent that will only grow worse unless things begin to change.