The conjunction of Jupiter and Venus

The week which marked the end of February and the start of March brought along not one but two fun astronomical spectacles: the planet conjunction and the northern lights. In this article, Almudena Visser Velez explains the conjunction of Venus and Jupiter.

The local planets Venus and Jupiter were clearly visible as bright pinpricks of light in the sky for about a fortnight, gradually nearing each other and coming to their closest on 1st March. This particular spectacle will next be seen in 2039, owing to the alignment of the positions of the two planets as they orbit the Sun. While these events do not have much astronomical significance, they are fun to look at.

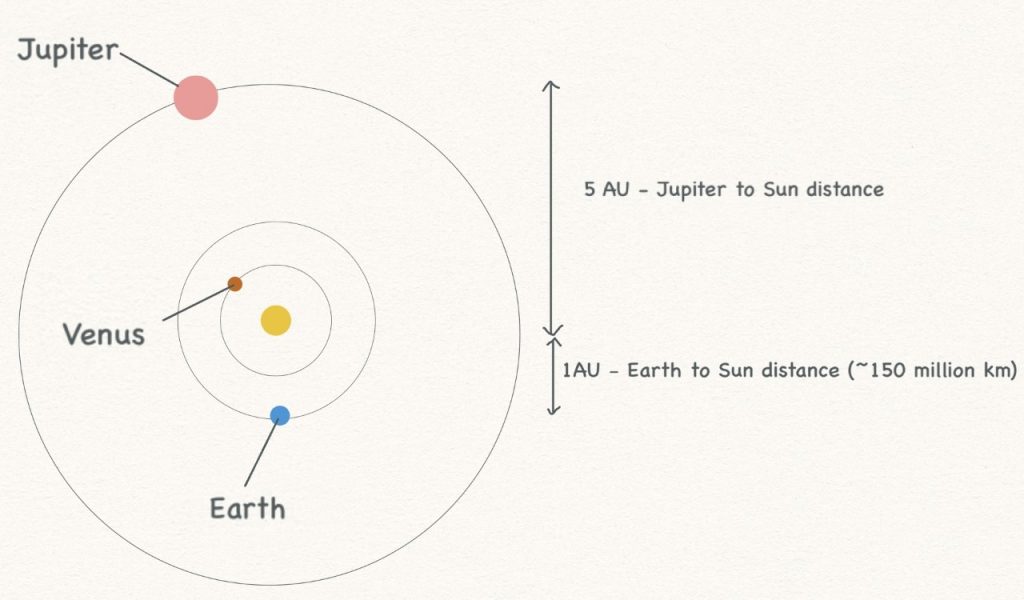

Venus, the rocky volcanic planet famous for its thick atmosphere and sweltering temperatures, is the second planet out from the Sun, and Jupiter, a much bigger gas giant, is fifth. Venus travels once around the Sun every 225 days, while far-out Jupiter takes a much longer 12 years to do so, on account of its larger orbit radius which clocks in at just over five times the distance between the Sun and Earth. The conjunction event, in which two planets appear closest to each other in the sky as viewed from Earth, is the result of their positions within their orbits roughly aligning in such a way that they appear to touch, even though the planets are huge distances apart. A small bird’s eye view sketch of the solar system, not to scale for practicality reasons, illustrates this below. It was not hard to spot Jupiter and Venus just after sunset in the early evening before the stars became visible, as the two planets appeared as bright nearby dots easily photographable with a simple phone camera, aided by the lack of clouds.

Above: From our line of sight on Earth, Jupiter and Venus appear almost directly aligned, despite being several hundred million kilometres apart.

The conjunction event, in which two planets appear closest to each other in the sky as viewed from Earth, is the result of their positions within their orbits roughly aligning in such a way that they appear to touch, even though the planets are huge distances apart.

While this event was visible to the naked eye for several days, some astronomers, amateur and

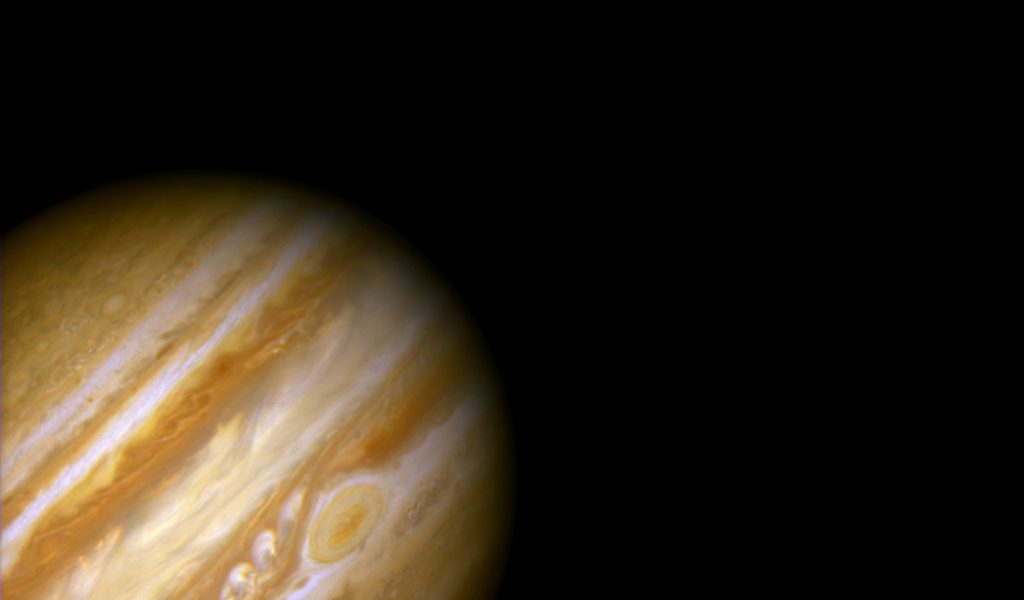

professional alike, managed to observe this via telescope. Below is a photo captured by Professor Bate of the University of Exeter’s Physics and Astronomy Department, with permission kindly granted, which shows both planets as well as some of Jupiter’s moons. An eight-inch telescope was required to spot the small moons, which would not have been visible to the naked eye.

Known as the Galilean satellites, Jupiter’s moons Callisto, Ganymede, Europa and Io are of important historical and scientific significance, as they were first observed by the astronomer Galileo Galilei in the early 1600s. It was largely thanks to this observation that the geocentric model of the solar system (with the Earth at the centre and other objects orbiting it) was replaced by the heliocentric model we know today (the Sun being orbited by the planets). Prior to this, it was commonly accepted that planets, and indeed the rest of the universe, revolved around the Earth. Galileo’s discovery of objects that were clearly orbiting a planet other than our own was controversial and deeply unpopular at the time for religious reasons. Nevertheless, as time went on and more observations were carried out, it became accepted that we are not the centre of the universe, merely one small part of it, thanks to four small spherical rocks orbiting a neighbouring planet.